7. A Very Yorkshire Christmas

A Very Yorkshire Christmas

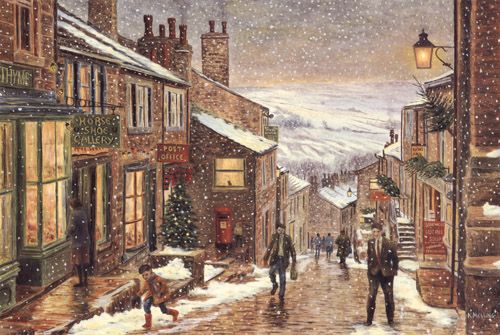

“Nowhere are

the traditions of Christmas kept up with such splendour as in Yorkshire.”

(Visitor to the county 1812)

Source: pintrest

Yorkshire is a

fantastic place to be all year round, but at Christmas it is extra special. It

has always been an area full of tradition, none more so than over the festive

period. Throughout history Yorkshire has provided some major contributions to

Christmas and the festivities surrounding it.

Roman York

A portrait of what Saturnalia could have looked like by Antoine Callet in 1783. Souce:wikipedia creative commons

The origins of

Christmas celebrations in Yorkshire date back as far as Roman Times and centred

on the city of Eboracum. The Saturnalia festival which took place from around

17th – 25th December was dedicated to Saturn, the god of harvest and

agriculture, which is something that resonated well with Yorkshire folk. The

festivities included a relaxing of the normal Roman society rules. The courts

were suspended, crime was more tolerated and even gambling was permitted.

Masters would serve their slaves a banquet of food and singing in the streets

was encouraged. Elements of the Saturnalia festival, such as over-indulgence,

merriment and singing are still at the heart of our Christmas festivities

today. These celebrations gradually changed from a pagan ritual to a Christian

one, due to the spread of the faith throughout the Roman Empire during the 4th Century. The

idea that the final day of Saturnalia, the 25th December also

marked the day of Jesus’ birth and this was first recognised by Pope Julius I

as Christmas started to take on a more religious theme.

Christmas in Medieval Yorkshire

Another strong

influence on Yorkshire Christmases came from both the Anglo Saxons and the

Vikings. The Danes’ Yule celebrations were also absorbed into the winter

festivities when Yorkshire came under the Danelaw in the 9th Century. This

placed more emphasis on marking the winter solstice, rather than celebrating

Jesus’ birth as the Vikings were pagan in belief. The word, “yuletide” is still

associated with the festive season today and the celebrations lasted for around

twelve days from the 21st December onwards.

Christmas

celebrations only took a more Christian turn again after the Norman invasion of

1066, when Christmas was celebrated in the third week of December. The word

“Christes Maesse” (Festival of Christ) was first used around this time and

William the Conqueror declared himself King of England on Christmas Day 1066,

which in his eyes was a further reason to celebrate, although probably not in

the eyes of Yorkshire folk back then.

Religion’s mark on

British and Yorkshire Christmases was more pronounced further in the later

Middle Ages, with church attendance and worship put at the forefront of the

festivities.

Since the 1400s a

tradition known as “The Devil’s knell” has taken place in the town of Dewsbury.

On Christmas Eve the All Saints parish church bells toll once for every year

since the birth of Christ. The peel is timed so that the last bell is rung

exactly at midnight on Christmas Day. This ritual is done to remind Satan that

Christmas resembles the beginning of his end. The ritual has only been missed

during the Second World War, when church bells were silenced for national

security.

All Saints Church in Dewsbury is the home of The Devil’s Knell. Picture credit: Stanley Walker creative commons

Carol Singing

In Medieval times

carol-singing was banned in churches because they disrupted the religious

services, so the vocalists would have to go elsewhere. Over the centuries, this

custom of carol-singing manifested itself in several ways. Some of them stood

outside in a circle near a prominent landmark in the town or village. Others

went from house to house collecting money and gifts from residents.

The sensible ones

congregated in public houses and taverns, where the added warmth and the

availability of ale helped to loosen their tongues in song. One such

carol-singing tradition still takes place each year at the Royal Hotel in the

village of Dungworth, near Sheffield. Over the past two hundred years singers

have congregated here every Sunday from mid-November to Boxing Day at noon for

a two hour sing. They sing a mixture of traditional carols and Yorkshire songs,

which are sung in the pub each week during the countdown to Christmas. Other similar

events across South Yorkshire take place in various pubs and venues from

mid-November onwards.

Yorkshire Christmas Food

Yorkshire has also

made several contributions to what we eat at Christmas time. The first turkeys

were brought over to England from the Americas by Yorkshire explorer William

Strickland in 1526. Originally from Marske, he built estates at both

Wintringham in Ryedale and Boynton Hall near Bridlington with the profits he

made from selling these exotic birds. William Strickland was the Bernard

Matthews of his day! The Strickland family crest, which adorns both of these

residencies is in the shape of a turkey, something which is widely acknowledged

as the first ever depiction of the bird in Europe. Boynton village church

lectern is also carved in the shape of a turkey instead of a traditional eagle

in honour of Strickland. The custom of eating turkey on Christmas day would

only become popular in the Victorian period, 250 years or so after Strickland’s

death in 1598.

Turkeys have been in Yorkshire since the 16th Century thanks to William

Strickland. Picture credit: The Kohsher creative commons

A natural addition

to any Christmas dinner is traditional Yorkshire pudding, which forms an

important area of the festive plate. Outside our great borders the debate rages

as to whether to include them or not, but as we know in Yorkshire it’s

compulsory! A slice of Wensleydale cheese can also be enjoyed with Christmas

cake and is a Yorkshire culinary tradition and said to date back to the 1890s.

The Yorkshire

Christmas pie has its origins in the 17th Century and

became popular during the Victorian period. The dish comprises of several game

birds including turkey, goose, duck, grouse, pheasant and pigeon. These were

layered with stuffing and encased in short crust pastry. Its links to the

county came when they were made in the large kitchens of Harewood House.

Naturally many of the birds which feature in the dish can be found on the

Yorkshire moorlands. Yorkshire Christmas pie was first served at Windsor Castle

in 1858 and became a Royal favourite.

A Christmas Carol

The Victorian era

saw a rejuvenation of Christmas celebrations, which had declined in the

previous two hundred years, largely thanks to a general banning of the festival

by the Puritans in the 1650s and other important religious dates in the

Christian calendar such as Easter taking more prominence.

The 19th Century saw

the emergence of similarities to how we celebrate Christmas today. Prior to

1837 and the accession of Queen Victoria to the throne, there were no Christmas

cards, crackers, trees or even holidays for workers, apart from on Christmas

Day itself.

One very famous

piece of literature was to change the festive season in the working class

industrial towns of Yorkshire forever. ‘A Christmas Carol’ by Charles Dickens’

was published in 1843, had one of the most profound influences of how Christmas

was celebrated and working class lives as a whole.

The common theme of

the rich giving to the poor ran throughout the book. Ebeneezer Scrooge, the

wealthy, mean industrialist becomes a changed man after being visited by the

three ghosts of past, present and future. Later in the story he gives a turkey

to Bob Cratchitt; one of Scrooge’s poor, underpaid employees and learns the

importance of being kind to his workers, especially at Christmas.

The middle and

upper classes of Victorian Britain who either read the novel, or saw it

performed through numerous stage adaptations had their consciences pricked

about their own treatment of the poor. The book was a factor in a boom of

charitable work done by the rich philanthropists over the festive period in the

years that followed and even helped to sow the seeds of social reform. One of

these measures was to make the day after Christmas a new public holiday, where

the workers would open up boxes given to them by their bosses. This became

known as Boxing Day.

While Charles

Dickens was not from God’s Own County his many trips to the then North

Yorkshire town of Malton to see his solicitor friend, Charles Smitheson had a

great influence on A Christmas Carol. Scrooge’s counting house was based on his

solicitor’s offices in the town, while St Leonard’s church is also represented

in the story.

The building in Malton which Scrooge’s counting house is based on.

Yorkshire can claim numerous

contributions to British celebrations at Christmas time. From bringing the

first turkeys to England, to carrying on ancient rituals and influencing A

Christmas Carol, it remains a special place in which to celebrate the festive

season.

Comments

Post a Comment